The Medieval Knights Templar

The Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon, more famously known as the Knights Templar, were

a military religious order formed in A.D. 1118 by nine French knights led by Hugues de Payens in order to

protect pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem, recently captured by western Christians during the First Crusade.

Each knight took a solemn vow before the Patriarch of Jerusalem to protect the new Christian kingdom. In

1119, King Baldwin II assigned to them quarters on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, the former al-Aqsa Mosque,

thought at the time to be the site of the Temple of Solomon, hence the name they came to acquire: pauvres

chevaliers du temple (Poor Knights of the Temple).

The Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon, more famously known as the Knights Templar, were

a military religious order formed in A.D. 1118 by nine French knights led by Hugues de Payens in order to

protect pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem, recently captured by western Christians during the First Crusade.

Each knight took a solemn vow before the Patriarch of Jerusalem to protect the new Christian kingdom. In

1119, King Baldwin II assigned to them quarters on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, the former al-Aqsa Mosque,

thought at the time to be the site of the Temple of Solomon, hence the name they came to acquire: pauvres

chevaliers du temple (Poor Knights of the Temple).

In order to raise funds for their support and recruit new members, Hugues returned to France, where his plan came to the notice of the most influential churchman of the age, Bernard of Clairvaux. Bernard championed the idea of milites Christi (soldiers of Christ) and wrote a rule for the new order based upon the reformed Rule of Benedict used by Bernard’s Cistercian Order. In 1129, the order was given official sanction by the Roman Church at the Council of Troyes. Ten years later, Pope Innocent II exempted the Templars from all local laws, which allowed members of the Order to move freely without having to pay tolls or local taxes and which effectively made them answerable to the Pope alone.

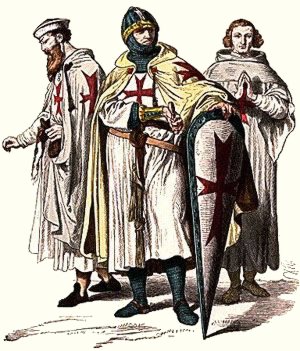

Christendom’s first warrior monks, the order’s new rule and official status required each knight to assume vows of poverty, chastity, odedience and service to God and the Church, as well as crusader vows to defend the Holy Land. They assumed the white habit of the Cistercian Order, to which they added a blood-red Cross. The most commonly used banner was bi-colored, black over white, known as the beauceant. The original Latin Rule composed by Bernard contained 72 edicts which governed virtually every aspect of the lives of the brethren.

The order was divided into military and non-military areas of responsibility. Those destined to fight in the order were divided into knights, heavily armed cavalry who were to be drawn from the knightly class, and sergeants, who formed light cavalry units. Non-warriors were given the responsibility to oversee the lands that were donated to the order in support of their crusading efforts. Chaplains were ordained clergy, who were to see to the spiritual needs of the brothers.

The popularity of the order ebbed and flowed according to the popularity of the crusading efforts of the time. The order acquired extensive land holdings through donation by which they funded their military activities in Palestine. It is impossible to know the size of the Order at any particular time. At its height in the thirteenth century, it may have included a thousand Preceptories, although only a small portion of the brothers would have been composed of knights. The Templars maintained no more than three hundred knights at its headquarters in the Holy Land, for instance. Still, their valor and ideals inflamed the imaginations of much of medieval Europe. Authors of tracts on chivalry and chivalric literature, as these emerged and were popularized in the twelfth century, used their conceptions of the Templars and other religious crusading orders as models to be emulated.

The Templars quickly became involved in more than protecting pilgrim routes. By the mid-twelfth century, their organization, training, numbers, and crusading devotion led them to become an elite fighting force in later crusading efforts.  Their Rule forbade them to surrender in battle so long as any crusading flag still flew and as such were formidable foes in battle. Their Muslim opponents normally classed them with the franj, the name given to Norman crusaders, knights who had attained an almost mythic status among the Saracens. Templars often were chosen to be the spearhead of a crusading army.

At the Battle of Montgisard in 1177, 80 Templars helped Baldwin IV and a small force defeat a much larger Muslim force under Saladin. Ten years later, Saladin returned the favor at the Battle of the Horns of Hattin, killing or capturing all of the Templar knights. Of the Christian knights captured, all were allowed the choice to convert to Islam, except the Templars and their cohorts the Hospitallers, who were ordered to be beheaded. No Templars were to be left alive to continue to fight. In an apparent act of solidarity, many non-Templar prisoners at the time claimed to be Templars and were beheaded as well. Most Templars no doubt viewed dying on crusade as a form of martyrdom, and in its last century, as Christian crusading efforts progressively failed, the Order's casualty numbers achieved staggering proportions.

Their Rule forbade them to surrender in battle so long as any crusading flag still flew and as such were formidable foes in battle. Their Muslim opponents normally classed them with the franj, the name given to Norman crusaders, knights who had attained an almost mythic status among the Saracens. Templars often were chosen to be the spearhead of a crusading army.

At the Battle of Montgisard in 1177, 80 Templars helped Baldwin IV and a small force defeat a much larger Muslim force under Saladin. Ten years later, Saladin returned the favor at the Battle of the Horns of Hattin, killing or capturing all of the Templar knights. Of the Christian knights captured, all were allowed the choice to convert to Islam, except the Templars and their cohorts the Hospitallers, who were ordered to be beheaded. No Templars were to be left alive to continue to fight. In an apparent act of solidarity, many non-Templar prisoners at the time claimed to be Templars and were beheaded as well. Most Templars no doubt viewed dying on crusade as a form of martyrdom, and in its last century, as Christian crusading efforts progressively failed, the Order's casualty numbers achieved staggering proportions.

The high cost of keeping an army in the field led the order to become involved in creative ways to raise funds. As an international armed force, the order was tailor-made for transporting money among noble houses or for safekeeping a nobleman’s property while that knight went on crusade. Templar houses accepted funds from pilgrims and gave letters of credit good for withdrawls at other Templar houses along the pilgrimage route, as the pilgrim needed them. Templar houses acted as safe deposit locations for royal and noble houses as well, for which the Order charged a fee. All of this financial activity has led modern scholars to consider the Knights Templar as among Europe’s first banking institutions. It also led some medieval observers to believe that the Poor Knights of Christ had become overly rich and overly powerful, a not uncommon complaint against religious orders who took vows of poverty but nonetheless owned great wealth. No doubt some of them acted arrogantly on occasion, which caused ill-feelings toward the Order and which led to occasion accusations of everything from usury to heresy. By the thirteenth century, the Order had indeed become the wealthiest single organization in Western Christendom, but modern scholars agree that the legendary hoards of the order were considerably exaggerated. The order’s main wealth, as opposed to that they periodically guarded, consisted chiefly of lands and buildings, crops and sheep, and the costs of continued warfare in the Holy Land continued to escalate in the thirteenth century as crusading efforts progressively faltered.

After the Siege of Acre in 1291, the crusaders were finally forced to evacuate Palestine, and the Templars established their headquarters on the island of Cypress. A large share of the popular blame for the loss of the Holy Land fell on the crusading orders, the Templars and Hospitallers, although the crusading ideal had been a hopeless dream for more than a century. Nevertheless, the new Templar Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, began touring Europe in 1292, attempting to raise funds and support for a new crusade. By 1300, however, the last efforts at maintaining a foothold in the East were lost, and the Order, for the first time in nearly two centuries, ceased to have a purpose.

It was just at this moment that Philip IV of France, deeply in debt and at war with England, decided to take advantage of current discontent regarding the Templars. He first attempted to get Pope Bonfice VIII to excommunicate the Order, but the pope refused and issued a stinging rebuke to the young French king. Philip, who was unhappy with Boniface for similar financial reasons, responded by having the pope kidnapped from his castle at Anagni and charged with sodomy and heresy. The pope was rescued by the people of Anagni but in a few years a struggle between Italian and French cardinals over succession to the See of Peter led to the famous Babylonian Captivity of the Church, resulting in the removal of the papacy to France and later to Avignon. The new French pope, Clement V, under heavy pressure from Philip, annulled all of Boniface’s official pronouncements against the king and reluctantly agreed to examine the Templars on charges of heresy, sodomy, and abuses of their privileges, the same type of charges which Philip had laid against Clement's predecessor.

Unwilling to await Clement’s investigation, Philip ordered all Templars within his domains arrested and their property siezed. This occurred early on the morning of October 13, 1307. It was a devastating public rebuke to the Order, since most observers did not understand that the move was financially motivated. Hysteria over the arrests ensued, particularly in Paris where mobs rose up against the Templars. Charges and counter-charges were thrown about. Ultimately, more than 100 charges were lodged against the Templars, expanding to such things as urinating on the Cross, holding secret rites, and devil worship. Most of the Templars arrested in Paris were tortured, and the majority of these confessed to one or another of these crimes. Almost no independent evidence or outside witnesses were produced to confirm their guilt; only their confessions exacted by torture.

Unwilling to await Clement’s investigation, Philip ordered all Templars within his domains arrested and their property siezed. This occurred early on the morning of October 13, 1307. It was a devastating public rebuke to the Order, since most observers did not understand that the move was financially motivated. Hysteria over the arrests ensued, particularly in Paris where mobs rose up against the Templars. Charges and counter-charges were thrown about. Ultimately, more than 100 charges were lodged against the Templars, expanding to such things as urinating on the Cross, holding secret rites, and devil worship. Most of the Templars arrested in Paris were tortured, and the majority of these confessed to one or another of these crimes. Almost no independent evidence or outside witnesses were produced to confirm their guilt; only their confessions exacted by torture.

Because of the resulting public scandal in Paris, and under pressure from Philip, the pope ordered the Christian monarchs of Europe to arrest the Templars and confiscate their property. A number proceeded against them, though it is doubtful that many thought they were actually guilty of the charges brought by Philip. A papal commission declared on June 5, 1311, that it found no evidence of heresy or other abuses by the Order, a decision seconded by the Council of Vienne. None of this mattered. Even before the commission reached a decision, Clement ordered the Order suppressed and its property be given to the Hospitallers, citing the scandal that had been created and the now limited usefulness of the Order. The Hospitallers, of course, never saw more than a small portion of the Templar’s assets. A great deal of property was never surrendered by the magnates who confiscated it. In the end, fifty-four Templars arrested in Paris renounced their confessions obtained under torture and were burned by the king as relapsed heretics, about half of those that had confessed. In March 1314, Jacques de Molay, Grand Master of the Order, and Geoffrey de Charney, Master of Normandy, publicly renounced their confessions as well and were burned to death on order of the king.

In its final years, the Order that had fought so long and hard for its faith, whose prestige and power had earned it equally powerful friends and enemies, and which had no doubt made telling mistakes over the years through arrogance or political naïvete, simply evaporated. In Portugal and Aragon, where the Reconquista was still active, newer military orders were created and staffed largely with former Templars. Many knights joined the Hospitallers. Others retired on pension or simply returned to secular life. In Scotland and other areas where papal influence was particularly weak, pockets of Templars may have been maintained for a time. However, the Knights Templar as a coherent religious military organization ceased to exist.

For further information on the medieval Templars, recent standard works include:

Ralls, Karen. Knights Templar Encyclopedia (New Page Books, 2007).

Newman, Sharan. The Real History Behind the Templars (Berkeley Trade, 2007)

Barber, Malcolm. The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Nicholson, Helen. The Knights Templar (Sutton Publishing, 2004).

All authors are professional medieval historians. Newman's book, a more popular treatment, also discusses many of the myths and legends that existed about the Order in its own time or grew up around it in modern times.

Return to History Page

Dallas Commandery No. 6 Copyright 2009. All rights reserved.

Please send any comments or questions regarding this Web site to: Commandery 6 Webmaster